In this in-depth portrait I present the life and career of Gene Tierney — the luminous actress who enchanted audiences with her haunting beauty and whose private life was marked by heartbreak, mental illness, and resilience. Below you will find a comprehensive chronicle that follows Gene Tierney from her privileged New York childhood through her meteoric rise in Hollywood, the tragedies that reshaped her life, the cataclysmic breakdowns and the slow, courageous recovery that followed, and finally her quiet later years.

Introduction: Beauty, Talent, Tragedy

“Look at her. Not bad.” That offhand line captures the almost casual astonishment Gene Tierney‘s presence inspired. As the documentary observes, she was “the embodiment of unattainable beauty, the image of perfection.” Yet the camera of fame never saw the whole story. Offscreen, Gene’s life was shaped by tangled family loyalties, betrayals, the ecstatic highs of artistic success, and a deep, private suffering that followed her for decades.

This article traces that life carefully, using documentary narrative as a backbone while situating events in broader context and exploring the emotional texture that made Gene both a magnet for devotion and a fragile figure in the glare of Hollywood. I write as if I were the documentarian, drawing on direct quotes and scenes to preserve the film’s voice while expanding where helpful.

Outline

- Early life and upbringing in Brooklyn and Connecticut

- Education and European influences

- Discovery, Broadway success, and move to Hollywood

- Early studio career and screen transformation

- Marriage to Oleg Cassini: passion, conflict, financial betrayal

- Motherhood, the tragedy of Daria, and the crushing guilt

- Career apex: Laura and Leave Her to Heaven

- Romances and liaisons—John F. Kennedy and Prince Ali Khan

- Mental collapse, treatments, institutionalization

- Recovery at Menninger, second marriage, partial comeback

- Later life, autobiography, and legacy

Early Life: “Princess” Born into the Jazz Age

Jean Eliza Tierney was born in Brooklyn on November 19, 1920, into an America that had just begun to breathe again after the shadow of World War I. The 1920s, the “Jazz Age,” set the stage for a childhood that began in comfort. She was nicknamed “Princess” by her parents — a foreshadowing of the way others would later treat her: admired, placed on a pedestal, and held to a high, sometimes unattainable, ideal.

Her mother, Belle Taylor, a former gymnastics teacher, passed down striking looks; her father, Howard Tierney, a decorated World War I veteran turned insurance broker, cast the household in a more disciplined mold. The documentary quotes Gene succinctly:

“My father was overly strict. He was the Lord and Master of the House.”

That single line tells us a great deal about the psychological climate of her formative years: obedience, duty, and the performance of propriety at home.

In 1926 the family moved to Greens Farms, Connecticut, into a sprawling home that outwardly signaled success. Yet beneath the veneer of this suburban affluence, the Tierney household seethed with tension. Gene’s childhood was haunted by the nightly quarrels between her parents; the documentarian notes how she “retreated into a creative world of make-believe,” a pattern common to those who turn to artistry for refuge.

Education, Early Talents, and a Taste of Europe

Gene showed early promise beyond mere looks. By the early 1930s she displayed gifts for writing and mimicry — talents that would later underpin her skill as an actress. Her father wanted a conventional life path for her: education followed by a respectable marriage. Still, he allowed one notable exception: when she was 15, Gene was permitted to study for two years in Lausanne, Switzerland. The documentary captures her mother’s memory:

“My mother loved Europe. She really enjoyed learning the French language. She made some wonderful friends and those were special days for her.”

These formative years abroad broadened her sensibilities and left her with a love for language, culture, and an early independence which would define her choices.

The Hollywood Encounter: Screen Tests and Broadway Triumphs

The family’s financial fortunes took a sudden turn after a lawsuit toppled Howard Tierney’s business and the family lost their home. In a desperate effort to maintain appearances, Howard sent the Tierneys on a road trip to the western United States in the summer of 1938 — a trip that would change Gene’s life.

On a Warner Brothers studio tour in Hollywood, a 17-year-old Gene caught the eye of director Anatole Litvak. He arranged a screen test and, despite Gene having no formal training, she was offered a studio contract at $150 a week. Although her father forbade her to accept immediately, Gene negotiated a bargain: once she completed her formal society debut, she could audition for Broadway in New York.

Broadway Ascendancy

On February 8, 1939, Gene made her Broadway debut in Mrs. O’Brien Entertains. Though the play itself was panned, critics singled her out for praise. She quickly won a more substantial role in James Thurber’s The Male Animal and, on January 9, 1940, became a Broadway sensation as an “ultra-modern coed.” Her charm and beauty were noticed by both critics and industry insiders; one observer in the documentary called her “an early Grace Kelly.”

That very performance led to the decisive moment: Darryl F. Zanuck, production chief of 20th Century Fox, saw her and issued an order that would redirect her career: “Sign that girl.” The Broadway-to-Hollywood pipeline opened for Gene, who held out for $750 a week — funds to be managed in a family corporation — and then left the stage to take on film work.

Hollywood Apprenticeship: Learning the Camera’s Language

At Fox, Gene was cast in the high-profile western The Return of Frank James opposite Henry Fonda. The documentary provides an intimate look at her early struggles with screen acting: at a preview she heard her own voice and recoiled, convinced it sounded like “an angry mini-mouse.” The Harvard Lampoon even named her the worst female discovery of 1940. Yet the film was a hit and Gene adapted quickly — smoking to deepen her voice, watching old films, leeching techniques from screen greats, and practicing tirelessly.

Her willingness to learn and her natural mimicry paid off. The film studio used the contrast of her exotic beauty and American debutante charm across a variety of roles: from seductive hillbilly in Tobacco Road to outlaw in Belle Starr to the exotic leads that later solidified her star image.

On-Set Diligence and Reputation

Colleagues remembered Gene as disciplined, generous, and hard-working: “Jean was very serious about becoming an actress and tried very hard not to upset anything, anybody,” the film recounts. She rehearsed lines late into the night and absorbed direction with a hunger that belied her fragile interior life. But success came with its pressures — studio interference in her personal life, a controlling father, and the paparazzi interest that follows a rising star.

Love, Rebellion, and the Cost of Independence

In December 1940, at a party, Gene met Count Oleg Cassini — an elegant and charismatic designer working for Paramount. Their affair developed rapidly; by their second date they were talking about marriage. But the romance faced opposition. Howard Tierney accused Oleg of being a fortune hunter and threatened to declare Gene mentally unfit. The studio pressured her into arranged dates. The young lovers separated briefly, but reconciled and defied both the family and Fox: on June 1, 1941, under an alias, Gene and Oleg married secretly in Las Vegas.

The consequences were immediate: Oleg lost his job at Paramount, Howard publicly threatened annulment, and Gene discovered that her father’s corporation — which held her earnings — was empty: Howard had taken their savings in a desperate attempt to save his failing business. “There was no money there. And that was a tremendous shock to all of us,” the documentary says. The betrayal cut deep; Gene vowed never to speak to her father again. Her family, once the firm foundation of her life, had fractured.

Career Momentum Despite Family Rupture

Despite the upheaval, Gene’s career accelerated. Her husband Oleg designed wardrobes for her films, and Fox began to cast her in more prominent and glamorous roles. She worked steadily, often filming while her private life spun in crisis. Yet the camera loved her: magazines featured her visage, and audiences responded to her mix of cool elegance and emotional depth. She became one of Hollywood’s most in-demand leading ladies by her mid-twenties.

Motherhood and a Catastrophe: The Tragic Case of Daria

Gene’s life seemed to tilt towards domestic happiness when she and Oleg expected a child during World War II. Oleg served in the US forces; Gene spent time traveling, visiting bond drives, and supporting wartime efforts. She enjoyed a rare domestic pleasure when she gave birth prematurely to a daughter, Daria, on October 15, 1943.

But joy turned quickly to devastation. Daria was born partially blind and, as the documentary explains bluntly, “was also deaf and severely retarded.” For a mother already carrying the burden of her husband’s infidelities and the stresses of stardom, the news was catastrophic. The moment of learning played as a shattering memory: Gene’s pain is conveyed in one recollection — she “started crying and screaming” and at one point ran out of the hospital. The film states plainly: “I don’t think Jean ever fully recovered from that blow.”

The Cruel Twist: Rubella, a Fan, and a Lifetime of Guilt

Months later, a chance confession by a female fan would land like a detonator. The woman — a former Marine — admitted she had secretly left her unit and visited the Hollywood Canteen while under quarantine for German measles (rubella). Gene had greeted service members at the Canteen just days before, and later discovered she had contracted rubella during pregnancy. The documentary articulates the moral horror of that realization: “The knowledge that it is your success that caused this tragedy to happen, how can anyone deal with that?” Gene’s feelings of guilt and anger tore at her psyche and became a pivotal turning point in her life.

Laura: The Film That Captured an Enigma

In the midst of this inner turmoil, fate offered Gene a role that would secure her cinematic immortality. The romantic mystery Laura (1944) cast her as an apparent murder victim whose portrait becomes an obsession for a detective (played by Dana Andrews). Critics and audiences alike were captivated. The film’s theme, by David Raksin, became a standard — a musical evocation of the spell Gene cast as the enigmatic Laura, “the face in the misty light.”

Her performance in Laura found a perfect match between role and persona: mystery, beauty, and an intensity that made the film feel inevitable. As the documentary puts it, “In the case of Jean Tierney, she was so exquisite that you just looked at her and you knew why Dana Andrews had fallen madly in love with her.” Laura was a box office smash; by age 24, after a dozen films, Gene was among Hollywood’s most sought-after actresses.

The Irony of Success

Success, however, did not cure the private wounds. Instead, it intensified them. The more Gene’s star ascended, the more personal cracks were exposed. Film sets, originally a refuge of discipline and craft, became arenas where her private anguish disrupted her ability to focus. Still, the public image remained magnetic: audiences saw only the calm, poised star, while the woman behind the mask spun in confusion and sorrow.

Leave Her to Heaven: Acting at the Edge

In 1945, Daryl Zanuck entrusted Gene with one of the most iconic roles of her career: Ellen Berent in Leave Her to Heaven (1945). The part demanded an actress who could portray obsessive possessiveness to the point of murder — a chilling inversion of Gene’s cultivated public style. She delivered a performance that critics praised as chillingly precise. The documentary captures the film’s suggestion that she had finally been given “one of the one in a million moments on screen.” The machine of Hollywood made her both dangerously beautiful and terrifyingly obsessive on-screen.

Leave Her to Heaven broke box-office records and earned the 25-year-old Jean an Academy Award nomination for Best Actress. It was a validation that she was more than a pretty face; she was a performer of depth and range. Yet by the time the accolades rolled in, her personal life was fragmenting further. The marriage with Oleg Cassini was unraveling under the weight of infidelities, arguments, and the unresolved pain over Daria.

Public Affairs, Private Crises: Jack Kennedy and Howard Hughes

While her marriage with Oleg deteriorated, other powerful men orbited Gene’s life. Howard Hughes, the reclusive millionaire, urged her to divorce and marry him. His attentions stoked dramatic confrontations: one night, Oleg confronted Gene while Hughes drove her home, igniting a violent chase that the documentary recounts with dark humor and intensity. The episode ends with physical assault and furious escape — a spectacle of passion and rage that reads like a noir subplot.

Another significant affair was the brief, intense relationship with a young Navy lieutenant named John F. Kennedy. A visitor to a set, Kennedy charmed his way into Gene’s life. She recalled him as “very courteous, very sweet,” “so bright and he’s such fun.” Their relationship blossomed and for a time Gene believed he would marry her. But after Kennedy’s election to Congress in 1946, he chose a different path, and Gene was left heartbroken — especially painful because she had told Oleg she would divorce him to marry Jack. The story provides an emotional parallel to the kind of tragic, romantic roles Gene often played on-screen: the illusion of an impossible love, the loss of a dream.

Decline: The Slow Unraveling

The late 1940s and early 1950s saw Gene trying to sustain an exhausting schedule of films while managing the personal fallout of failed relationships, worries about finances, and the unresolved sorrow of Daria’s institutionalization. In November 1948, she gave birth to a healthy daughter, Christina, but the shadows of Daria’s condition lingered — the financial responsibility for Daria’s care and the burden of supporting Oleg’s budding fashion enterprise added weight to an already precarious emotional state.

The Dangerous Charm of Prince Ali Khan

During a Parisian trip in the early 1950s, Gene embarked on a relationship with Prince Ali Khan — a charismatic, globe-trotting bachelor and the son of the Aga Khan. For a woman searching for escape and excitement, Ali seemed to offer the exotic life she craved. Yet the romance demanded choices she could not accept: Ali’s father publicly opposed the union, and the prince’s proposal required Gene to relocate to his country, convert to his religion, and sever ties with her family — a condition that was unthinkable for someone who had built her identity around family loyalties.

Gene was torn. The documentary describes her as being “just absolutely torn.” On one side was the allure of a thrilling new life; on the other, the memory of her father, the devotion to her mother, and the deep ties that defined her. The pressure fractured her mental equilibrium.

Mental Collapse: When the Mask Came Off

By 1954 Gene’s ability to function was deteriorating. She began to forget lines, to become disoriented on set, and to write rambling letters accusing colleagues of conspiracies. The documentary captures this decline with stark honesty: “She would go in and out of these periods,” and Gene herself is quoted: “I know when I’m slipping. It’s just like falling down a manhole and not having anything to grab onto.”

Audiences remained unaware, but behind the scenes things were alarming. While rehearsing for a television appearance, Gene collapsed, then withdrew from public life. She locked herself in her mother’s New York apartment and began to hallucinate. Family members eventually took her to psychiatric care; she received electric shock treatment (ECT) at the Harkness Pavilion and later at the Institute of Living in Hartford, Connecticut.

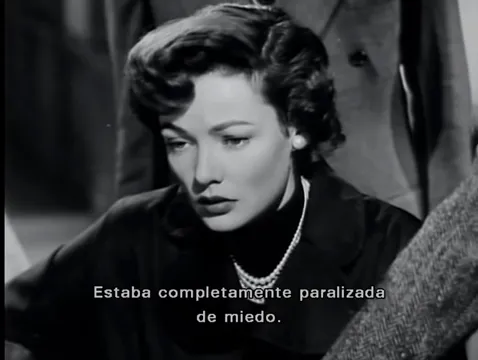

Electric Shock Treatment and Institutional Trauma

The documentary provides an unflinching account of this period. Gene feared the procedure: “She was absolutely paralyzed with fear,” the narrator says. The ECT sessions were traumatic — the documentary notes she was strapped down and that the shocks “just shattered the brain” and left her with patchy memory. After an initial series of treatments she spent nights screaming in locked rooms that felt like cells. Twenty more shock treatments further eroded her memory and left her dazed. On one occasion she walked out onto a fourteenth-floor ledge before stepping back inside; police intervened, and she was taken to her third mental hospital.

This period is perhaps the darkest in her life. The image of the glamorous star reduced to a patient in a locked ward upends the old Hollywood fantasy. The film does not shy away from the stigma and the brutal realities of mid-century psychiatric care, but it also shows the beginnings of a path forward.

Recovery: Menninger, Menial Work, and Relearning Life

The turning point came at the Menninger Clinic in Topeka, Kansas. There, new medications and a more humane approach allowed Gene to begin processing her grief and illness. The documentary highlights the clinic’s role in helping her see that “it was not such a horrible thing to be sick and to have mental illness.” Therapeutic work, structure, and respect gave her a sense of self beyond the celebrity persona.

Released in 1958, Gene retreated to Aspen for a vacation — and met Howard Lee, a gentle oil executive who accepted her past and did not judge her psychiatric history. They married on July 11, 1960. The new marriage was a stabilizing influence: Howard was “soft-spoken and gentle,” the documentary states, offering the emotional containment Gene had lacked for many years.

Step-by-Step Re-entry to Life

At Menninger, an important part of recovery was re-engagement with mundane life. Gene took a job as a saleswoman in a dress store in Topeka. The image is humbling but instructive: people were surprised to find a movie star as a shop clerk, but Gene found dignity and pleasure in simple routines. She discovered a social normalcy in shopping, chatting, and doing work that was ordinary yet meaningful. The press interviewed her during this period and she spoke candidly about her experiences — a brave act at a time when psychiatric illness was stigmatized.

A Partial Comeback and the Fragility of Return

By 1959 Gene had been released from Menninger “days before her 39th birthday,” and with Howard Lee at her side she felt ready to return to acting. Otto Preminger, director of Laura, cast her in Advise and Consent (1962) as a Washington hostess — a role that returned her briefly to the political and cinematic circuit. The documentary notes an evocative scene: after filming she and Howard had lunch at the White House where she sat next to John F. Kennedy. She told him she was happily married and that “when she went crazy, he still loved her.” It was a bittersweet reconciliation with a past that had once promised more.

Her final feature film appearance came in 1964 in The Pleasure Seekers — a minor role that made Gene realize the world of stardom had passed her by. She finally accepted that her era had ended. The documentary captures her relief: she resolved not to continue pushing herself to reclaim what was no longer there. There is dignity in that acceptance: after a life of striving and suffering, she chose peace.

Later Years: Quiet Domestic Life, Memoir, Loss

Gene and Howard moved to Houston, Texas, where she embraced a quiet domestic life she had never been able to enjoy in her earlier years. She relished small pleasures: grocery shopping, lunches with friends, playing bridge, and the routines of being a housewife. The documentary emphasizes this as a form of healing — the ordinary as balm.

Encouraged by her family, she wrote her autobiography, Self-Portrait, published in 1979. The book is a candid testament to survival and recovery, and an attempt to reclaim her narrative from the tabloid renderings that had often miscast her life as merely scandalous.

The Final Losses

In 1981 Howard Lee died. Gene fell gravely ill with grief; those closest to her feared she might not recover. Still, she persevered for another decade, living privately in Houston. The documentary says she “still suffered occasional bouts of mental confusion” and describes the little quirks of aging — the late-night phone calls about meeting at odd hours — as echoes of an earlier life that never fully vanished.

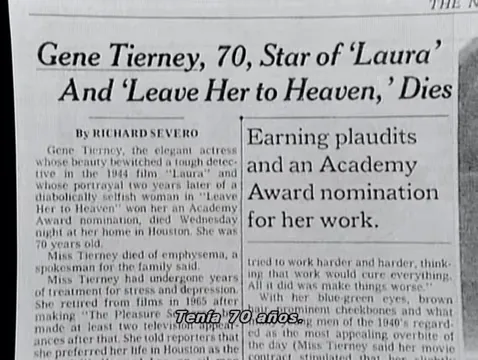

On November 6, 1991, after decades of heavy smoking, Gene Tierney succumbed to emphysema at age 70. The end of her life was quiet, but her loss resonated widely. Fans mourned not only the beauty on-screen but the luminous talent and the woman who had endured so much behind the façade.

Legacy: The Unlucky, Lucky Girl

How should we remember Gene Tierney? The documentary offers a poignant summation: “There was a wonderful girl that was battered by destiny. It appeared that everything had been given to her. And suddenly at a certain moment in her life, luck ended. She was the unluckiest, lucky girl in the world.” It’s a paradoxical phrase because Gene’s life was undeniably blessed — beauty, fame, artistry — yet repeatedly punctured by misfortune: a traumatic family betrayal, a daughter born gravely ill, the pressures of stardom, and devastating mental illness.

Her films remain a testament to her artistry. From Laura to Leave Her to Heaven, Gene created characters who were both dangerous and fragile, luminous and mysterious. She was one of those rare performers whose presence carried an ineffable charge: the audience could never fully articulate it, but they felt it. That blend of glamour and vulnerability became her signature.

Why Her Story Still Matters

Gene’s biography resonates today for several reasons. First, it exposes the human cost of fame and the way the studio system — and the public’s appetite for spectacle — could exacerbate fragility rather than protect it. Second, it highlights the social stigma surrounding mental illness in mid-century America, and how treatments like ECT were both life-saving for some and damaging for others. Finally, her recovery story — the humane approach at Menninger, the grounding in ordinary work and loving partnership — offers a humane model of rehabilitation that emphasizes respect and dignity.

Her autobiography Self-Portrait (1979) remains an essential document for anyone seeking to understand the lived experience behind the screen image. In her own words and through the reflections of friends and family, we see not only the celebrity but the daughter, mother, lover, and ultimately, survivor.

Filmography Highlights and Notable Performances

- The Return of Frank James (1940) — one of her first major studio roles that introduced her to cinema audiences.

- Tobacco Road (1941) — a John Ford film where she played against type as a seductive hillbilly.

- Belle Starr (1941) — a Western showcasing her versatility as an on-screen outlaw.

- The Shanghai Gesture (1941) — marked by Oleg Cassini’s designs and her exotic screen presence.

- Laura (1944) — the role that defined her mystique and made her a star.

- Leave Her to Heaven (1945) — a chilling portrayal of obsession that earned an Oscar nomination.

- The Razor’s Edge (1946) and The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947) — performances that showed emotional range.

- Night and the City (1950) — a film noir that highlighted her dramatic intensity.

- Advise and Consent (1962) — a later-career role that marked her partial return to film.

- The Pleasure Seekers (1964) — her last feature film role.

Key Quotes That Encapsulate Her Life

- “Look at her. Not bad. She was the embodiment of unattainable beauty, the image of perfection.”

- “My father was overly strict. He was the Lord and Master of the House.”

- “The knowledge that it is your success that caused this tragedy to happen, how can anyone deal with that?”

- “I know when I’m slipping. It’s just like falling down a manhole and not having anything to grab onto.”

- “She was the unluckiest, lucky girl in the world.”

Reflections: On Talent, Tragedy, and Compassion

Gene Tierney’s life prompts questions about how society treats people who are both brilliant and vulnerable. She was given cultural adoration for her beauty and artistry, yet the same culture was slow to recognize the depth of her suffering or provide compassionate, effective care. The arc of her life — privilege, success, catastrophe, recovery — is, in many ways, representative of the 20th-century celebrity experience. Her story invites empathy rather than voyeuristic pity.

She lived through eras defined by evolving medical practices and changing ideals about mental health. The brutal ECTs she endured early on seem, in retrospect, emblematic of an era that often prioritized expedient “fixes” over a patient-centered understanding of trauma and grief. Menninger’s more humane care later in her life hinted at a better way forward: therapy, medication when appropriate, structure, and respect for the whole person.

Gene’s later years, in which she embraced ordinary life and wrote openly about her struggles, represent a powerful counter-narrative to the myth of the invulnerable star. Her willingness to speak publicly about mental illness — at a time when most kept it secret — helped destigmatize a condition that affects millions.

Conclusion: Remembering Gene Tierney

Gene Tierney remains an unforgettable figure in American cinema: a woman whose face and performances embodied a rare combination of ethereal beauty and emotional intensity. But to condense her into an icon is to miss the human complexity beneath. She was a daughter, a mother, a wife, a lover, an artist, and a patient. Each of these roles added layers to her life and, at times, exacerbated her pain.

The central lesson of her biography is less about scandal than about resilience. Despite humiliation, heartbreak, and the ravages of mental illness, she rebuilt a life anchored in quiet affection, honest work, and authorship of her own narrative. The “unluckiest, lucky girl” phrasing feels apt — she experienced almost every imaginable fortune and misfortune, often simultaneously.

Her films continue to be studied and enjoyed, and her autobiography offers an intimate, candid account of what it feels like to be torn between image and interior life. For those of us who treasure classic cinema, Gene Tierney remains a haunting presence — a reminder that the faces that mesmerize us on-screen are human beings with histories that demand compassion and understanding.

If you want to revisit the documentary that inspired this article, it was produced by Cinecinéfilos Bio, and it offers an elegant, somber, and compassionate portrait of a complicated life.